The science policy behind Brazil's agricultural triumph

Embrapa made Brazil a world leader in agriculture. What can we learn from it?

Eliseu Alves discovered his unwelcome nomination to government on the radio.1

It was 1972, and Alves was ready to leave Brazil. He had returned to his home country after finishing his PhD in agricultural economics in the US for what was meant to be a short stay – he had lined up a professorship at Purdue University. Along with a working group of Brazilian agricultural researchers, Alves proposed that the Brazilian government establish a new agricultural research corporation, Embrapa, that would focus on problems specific to the country and equip farmers with the knowledge and technology to transform Brazil’s stagnant agricultural sector. The government accepted the proposal and asked Alves to be Embrapa’s second-in-command. He declined. It was a rude shock, then, to hear his nomination to Embrapa announced on the radio only days later.

When Alves returned to Brasilia, the military government informed him that he could resign from his appointment, but then he would never work in Brazil again. Reluctantly, Alves accepted the position, intending to leave quietly after a couple of years. Instead, he stayed for twelve years, guiding Embrapa through its first decade and overseeing its transformation of Brazil’s agriculture.

This is the story of how Embrapa transformed Brazil from a food aid recipient into the world's agricultural superpower, and what it reveals about the marriage of science and political will. It’s a story about betting your budget on sending scientists to the US for their PhDs, even when you're under pressure to produce immediate results. It's about running TV ads with cattle marching into Sao Paulo to keep politicians from cutting research funding. It’s a lesson in how developing countries can build world-class research institutes that transform their economies, and it’s a lesson on how the US can turn science towards its industrial policy objectives.

Brazil’s agricultural transformation

In 1960, Brazil was poor, with a GDP per capita roughly equal to Nigeria's today. Despite being an agrarian economy, Brazil was actually a major food importer and even a recipient of US food aid.

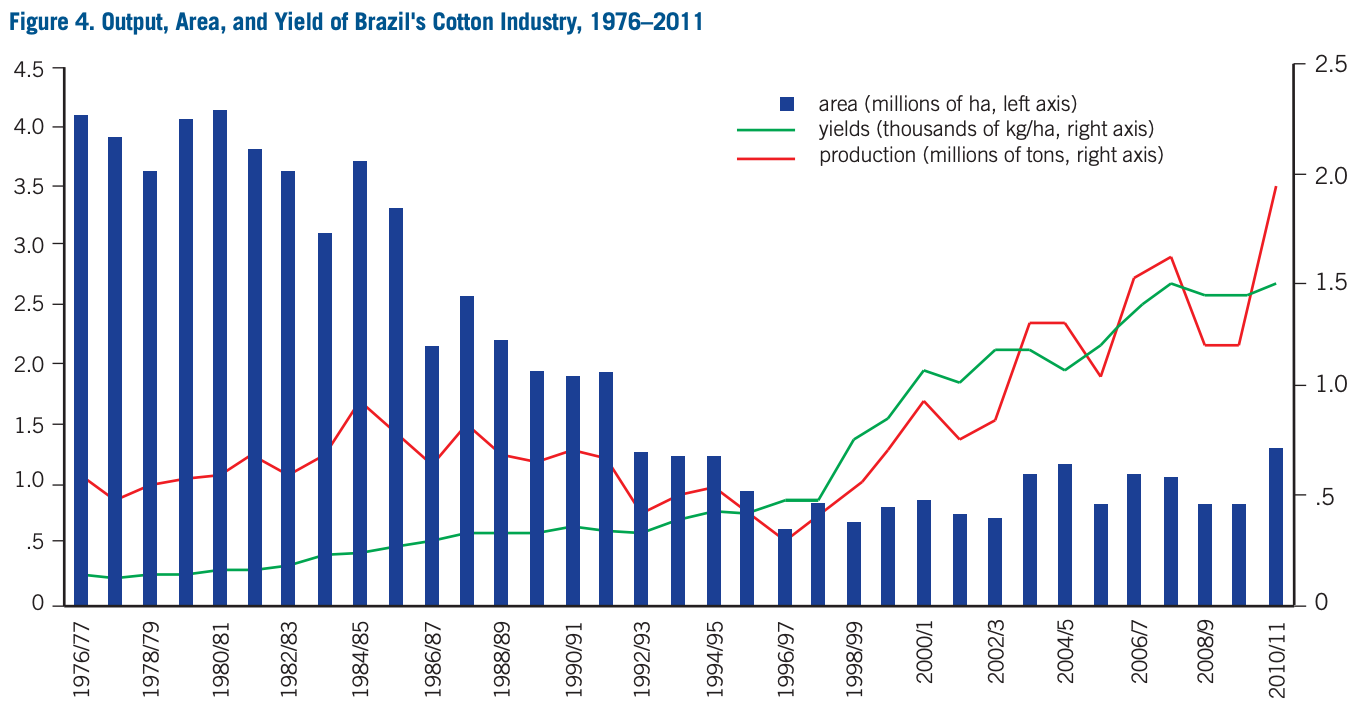

But today, Brazil is the world's biggest agricultural exporter. While the country has not reached high-income status – its growth has been slow in manufacturing and services – its agricultural productivity growth has been extraordinary. Brazil is now the world's largest exporter of soybeans, coffee, sugar, orange juice, and beef, and a leading player in corn, cotton, and pork. This transformation has occurred primarily through yield growth, rather than through expanding farmland. Brazil has quadrupled yields across leading crops since 1960 – faster than the United States, despite the US’s much higher agricultural R&D spending.

There wasn’t a single slam-dunk cause for this transformation. Brazil adopted a subsidized credit scheme for farmers who adopted modern equipment/fertilizer/high-yielding seeds, which helped transform the way agriculture was done from being just about small-scale farms. They had functioning land markets, so more productive farmers could expand their area of cultivation and boost overall productivity. They had a robust fertilizer industry due to both protectionism and induced demand from subsidized credit. All of these factors would deserve their place in a full story of Brazil’s agricultural transformation.2

But these are all factors that development economists already emphasize when discussing how countries can modernize. They are part of the standard playbook: subsidize farmers to adopt modern inputs and fix market failures. Basic steps that fit a “backwards” country.

Establishing a world-class research institute to advance the frontier of knowledge in agriculture is not part of that playbook. Yet that is exactly what Brazil did in establishing Embrapa. And against the odds, they succeeded. That is why I’m telling the story of Embrapa today.

Embrapa’s history

Brazil’s status as a food importer and a recipient of food aid was a high-priority problem for its military dictatorship, installed in 1964. It made the country vulnerable to being internationally pressured, and it was a dangerous source of population unrest. As a result, securing Brazil’s food independence was a high priority for the new government.

A natural focus was to build out rural extension. Rural extension is the system through which agricultural knowledge and best practices are transferred from researchers to farmers through field agents who teach modern farming techniques. Brazil already had rural extension infrastructure from the 1950s, built with American collaboration. But this extension simply didn’t work. Before his PhD, Eliseu Alves worked at ACAR-MG, the rural extension corporation of Minas Gerais state, and evaluated the organization’s impact on farmers for his master’s thesis. He concluded that farmers with ACAR-MG’s assistance did no better than farmers without it. Remarkably, his supervisors and colleagues agreed with his conclusions, but simply shrugged – they didn’t know what to do better. It was an open secret that rural extension was not working in Brazil.

But why?

A working group of agricultural researchers, led by sociologist Jose Pastore and Alves, identified a lack of applicable knowledge as the problem. Rural extension was based on the knowledge taught by American agronomists: knowledge cultivated in Iowa and Wisconsin, not in Mato Grosso or the Cerrado. That temperate advice withered in the tropical heat, and extension agents didn’t know how to answer farmers’ questions.

The working group concluded that they needed to create new, Brazil-specific knowledge for farmers. Thus, they created the blueprint for a new organization: a state-owned company that would conduct agricultural research with a clear mission to solve Brazilian problems, respond to farmer demands rather than academic curiosity, and maintain its focus through centers organized by crops and biomes rather than scientific disciplines.

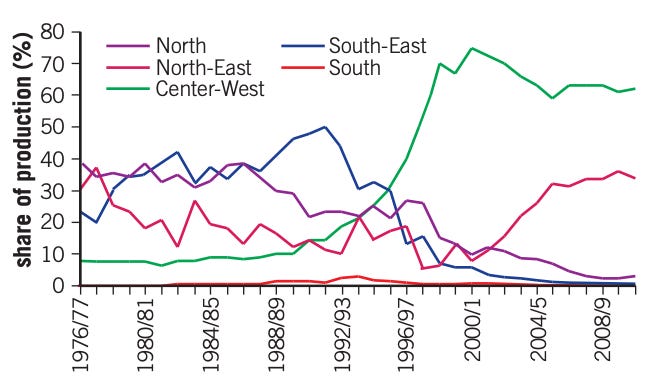

Embrapa’s first significant win came in the Cerrado. The Cerrado is a massive biome in western Brazil, three times the size of Texas, and almost all of it was available for farming. But farming was practically absent from the Cerrado, because its soil was too acidic and nutrient-poor for crops to grow, and its climate was hotter than Brazil’s subtropical south, where farming was widespread. To make the Cerrado arable, Embrapa started an agricultural liming campaign – treating the soil with limestone-derived chemicals to reduce soil acidity. They also developed a new soybean variety that was tolerant of the Cerrado’s harsh climate, unlocking new possibilities for growing soy, a profitable cash crop. Today, the Cerrado hosts 70% of Brazil’s beef cattle and 50% of Brazil’s soy production, both of which are key to Brazil’s agricultural exports. And Brazil’s center-west region, of which the Cerrado is the biggest biome, has become the largest area of Brazilian agriculture.

Embrapa continued to rack up victories: developing varieties of rhizobium bacteria that could fix nitrogen in tropical soils and reduce the need for fertilizer, cross-breeding African grasses to create pastures that produced twenty times the yield of cattle feed, and creating no-tillage crop management systems that preserve soil health. Since its founding, Embrapa has created over 350 cultivars and filed over 200 international patents. It hosts the largest gene bank in Latin America and one of the largest in the world. It is, in short, one of the most cutting-edge agricultural research institutes on the planet.

So how did Embrapa do it?

Lesson 1: Invest in human capital

Suppose you’re in charge of a brand-new research institute in a poor country, with the intimidating goal of transforming the country’s agriculture. You are under intense pressure to generate results, your organization’s continued existence is not guaranteed, and you have a tiny base of researchers to draw on – in 1975, Embrapa had only 28 researchers with PhDs. What would be your first priority?

You might throw all your researchers and money at one problem, prioritizing one area for a major push. That strategy could pay off – with a small but brilliant team, you could conceivably make some progress, thus living to see another fiscal year. But your ambitions would be strangled by the reality of having too few researchers to actually do research. Embrapa’s mission was to create knowledge with clear economic relevance to Brazil, and producing knowledge is really hard, let alone directing that research effort towards a specific topic area. (Just ask your favorite graduate student!) Without investing in your researchers, in a few years, your institute’s research outputs would dry up. Politicians would come knocking, asking you five things you did in the past week. Cue the game over screen.

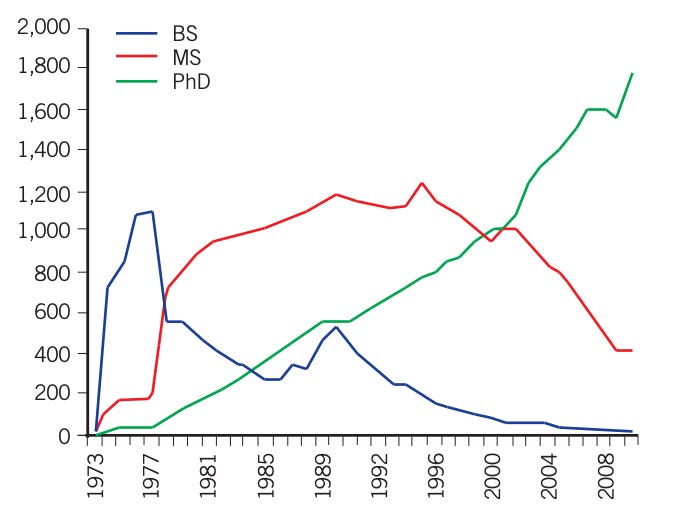

What you would probably not try to do is immediately start spending huge sums of money on sending your research staff to do advanced research degrees, before they do any actual research for you. But that is what Embrapa did. In its first ten years, Embrapa spent 20% of its budget paying for its staff to get advanced degrees in agricultural science, at universities in the US and Europe. By 1988, it had more than 1,000 researchers with PhDs, most trained abroad on Embrapa’s dime. In the graph below, it’s visually obvious when all the researchers with bachelor’s degrees get master’s degrees, and then later get PhDs. (source)

It would be a minimum of 3-5 years before any of these researchers could return and do any useful research, making it a risky investment for an institution that might not even exist in 3-5 years. But Alves, who created Embrapa’s research training policy, was a sophisticated student of Chicago economics. His doctoral advisor, Edward Schuh, had done his own PhD under Gary Becker and Theodore Schultz at the University of Chicago – the originators of human capital theory, a view so ubiquitous among economists today that it isn’t even called a “theory” anymore. Human capital theory views people’s skills as analogous to physical capital – in particular as a resource which can be invested in, and which has compounding returns over time. Viewing people’s skills as capital pushes you to invest in building up a stock that will compound over the long run, rather than spending it all down at the very beginning out of desperation.

This was exactly the strategy Alves followed, in focusing on training. The quality and quantity of its researchers was essential to why Embrapa could make breakthroughs like liming the Cerrado and creating new soybean varieties that would grow in tropical soil – breakthroughs that would have been out of reach for Embrapa’s original research team, as small and untrained as it was.

An important part of this pipeline was ensuring that Embrapa’s research staff was actually well-equipped to benefit from this training. Embrapa started by hiring the brightest graduates from Brazil’s universities – not a difficult task, because they paid handsomely, and because the labor market was weak. The very best of these new hires were sent off to do advanced studies immediately; the rest were given a couple of years of training within Embrapa, learning on the job and through internal seminars. The internal skill-building also occurred through frequent collaboration with foreign researchers, who would give talks at Embrapa and advise its staff, especially on breakthroughs that had been made elsewhere that Embrapa could build on. This was a complete human capital pipeline, a system for generating large numbers of world-class researchers who could tackle Brazil's specific agricultural challenges.

Lesson 2: politics, politics, politics

Reading the section above, you might conclude that Brazil’s government was saintly in its wisdom and foresight, allowing Embrapa to make long-term investments like sending its research staff to do PhDs in the US.

You would be wrong.

When Embrapa began its training policy, it was vigorously opposed by the minister for agriculture, to whom Embrapa reported. But Alves called up a colleague who was close friends with the president, and the president overruled the minister, declaring that Alves called the shots at Embrapa.

This was part of a broader pattern; Embrapa’s leaders ensured that they were always friendly with people in power, so that they would be free to make patient or difficult decisions. This was essential, in an environment where even valuable agencies could be dismantled by political winds. That reality was made very clear by the case of Embrater, a sister agency that worked on rural extension and diffusing Embrapa’s knowledge to farmers. In 1989, an influential group of officials within Embrater supported Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in the presidential election. But Lula lost, and the new president, Fernando Collor de Mello, promptly shut Embrater down. Embrapa avoided this mistake, always cultivating allies and never picking fights.

But avoiding partisan politics didn't mean avoiding politics altogether. Embrapa invested heavily in political capital through strategic communication. The institute created a sophisticated communications department, even paying for communications professionals to earn advanced marketing degrees. It published glossy press releases, hosted seminars for journalists to hear about Embrapa’s research, and mandated that scientists give interviews to reporters – a deeply unpopular policy with those scientists, but one that paid off in public visibility.

Embrapa even ran full-blown public advertising campaigns. On its 10th anniversary, Embrapa aired a campaign on state television showing a herd of cattle entering Sao Paulo, with the caption ‘the results of Embrapa’s research are coming to town.’ The message was clear: we at Embrapa are making your food cheaper, so keep us generously in your hearts and in your budgets. Alves put it bluntly: “We were always in the press publicizing [Embrapa]. Without publicity, we would be dead.”3

This focus on politics was built into Embrapa’s structure from the beginning, in the decision to establish it outside of the university system. Brazil’s American advisors had pushed for Embrapa to be housed inside the university system, echoing how America’s agricultural research ecosystem started from land grant colleges that evolved into universities. But Embrapa’s founders resisted. Partly because it would have made focused research difficult (more on that below), but also because Brazil’s universities were broadly antagonistic to the military dictatorship. If Embrapa had been associated with the university system, it would have been intensely scrutinized by the military, and susceptible to the partisan impulses that would later result in Embrater’s downfall. It was established outside the traditional research ecosystem in order to always be on the winning side of politics.

This vision contrasts sharply with how we normally think about science policy. In our mental model, the goal is for science to be insulated from political pressures, so that scientists can work on what is most important rather than responding to parochial concerns. But that was just not an option for Embrapa, who needed to be savvier than anyone who would see them defunded. Alves would never have been caught off-guard by politicians complaining about shrimp on treadmills.

Lesson 3: respond to market demand

An applied research institute has a more complex task than you might expect. “Do socially relevant research” sounds like a good guiding principle, but it could easily lead to a fragmented and ineffective mission. For one thing, Brazilian agriculture had a very large number of potential focus areas – many crops that were cultivated and could use research, many potential technologies that could benefit farmers if created. In addition, scientists left to their own devices will do research that they find interesting, and will argue its social relevance after the fact (just ask your favorite grad student again!)

So instead of letting their attention be fractured across too many areas or driven by the interests of its researchers, Embrapa leaned into induced innovation, an influential concept among agricultural economists.4 Put simply, agriculture has three inputs into production – land, labor and intermediates (e.g. fertilizer). To make agriculture more efficient, we need to focus our innovation on one of these three inputs – reducing the need for one of them, and thus reducing costs. But which one should we focus on? Induced innovation says that we should focus our efforts on the input that has the highest price. Intuitively, the biggest cost reduction comes from focusing on the most expensive inputs.

In Brazil, that meant focusing on land. Agriculture had flourished in the south, around Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. But those regions were running out of frontier land as they rapidly urbanized. As a result, land was becoming expensive – and that land cost was showing up in the price of output, making Brazilian commodities more expensive and unable to compete in global markets. Thus, tackling the high price of land thus became Embrapa’s focus. By increasing the supply of arable land, they would reduce the price of agricultural land, both increasing the quantity that Brazil could produce and reducing the price it would sell for. This was the reason why they focused on making the Cerrado arable – the initial victory that established their value to Brazilian agriculture.

Organizational structure reinforced this market focus. Embrapa organized research centers by crop and biome rather than by discipline, making it easier to direct research towards specific priorities. There was pressure to make each center serve all crops grown in its region, but Embrapa resisted, knowing that specialization was essential for progress with limited researchers. This structure made it possible to respond to market signals that were crop-specific – for example, they could direct research towards new soybean varieties because of the rising global price of soy.

The focus on market demand gave Embrapa a clear direction, ensuring that every research breakthrough had a clear path to improving farmer productivity and Brazil's agricultural competitiveness.

So what can we learn from Embrapa?

Embrapa’s history is clearly a success story, but what does it tell us today about science policy?

I think the wrong lesson would be to follow Embrapa’s decisions. Those decisions were the product of its context. It invested in training researchers because Brazil needed more researchers. It prioritized increasing the amount of arable land over (for example) creating better fertilizers or improving crop management because land was the binding constraint that Brazil faced at the time. It was set up as a corporation to allow for more flexible contracting and higher salaries than could be found in government agencies. These decisions would not necessarily make sense in every country and context.

But what I think we should take away is the importance of the forces that Embrapa cared about. Consider the lesson of being politically conscious. Of course, what that means would look very different for (say) the National Science Foundation than what it looked like for Embrapa. Applied agricultural research is intrinsically easier to sell than basic research, even if basic research is more useful. So while it might fall flat for the NSF to run a Super Bowl ad about its research, we should consider it a virtue for our science agencies to be able to navigate political firestorms and advocate for themselves. We are living with the consequences of our scientific institutions being politically naive.

The other lesson I think we can draw is about the utility of directed research programs as an industrial policy tool. Embrapa was set up following an economic directive – to make Brazil a powerhouse in the agricultural sector. And it achieved that by building up the knowledge that Brazil needed to make its agriculture much more productive. This rhymes with the industrial policy motivations that countries have today. The US wants to become a world leader in producing chips, or to increase its manufacturing capacity? Instead of blunt force instruments like tariffs, it could create the largest directed research program in history to ensure that it has the scientific knowledge to produce more sophisticated goods than other countries. This has the advantage of being positive-sum, creating knowledge for the world as a whole, while still helping enshrine American advantage.

Vannevar Bush, the founder of the NSF, forcefully argued for it to focus on basic scientific research, with no direction other than that chosen by scientists themselves. “A nation which depends upon others for its new basic scientific knowledge,” he argued, “will be slow in its industrial progress and weak in its competitive position in world trade, regardless of its mechanical skill.” This position has weakened over time, and the NSF does fund applied research. But it remains verboten to simply direct research efforts – both funding and researchers – on a large scale towards policy priorities. I think this is a mistake, and Embrapa shows that applied research institutes can be powerful.

This quote comes from Alves’s biographical interview published by Embrapa. The original is in Portuguese, but I used a machine translation service to extract the relevant chapters. This interview is my primary source for almost all the claims in this essay about how Embrapa functioned. I would rather rely on academic sources than on the stories of a man who was certainly not neutral, but almost all the academic sources I’ve read also cite Alves’s writings when discussing Embrapa’s internal workings, making them no better. The only other primary source I’m aware of is a memoir by Jose Irineu Cabral, the first president of Embrapa, which I have not read.

A reader who wants that full history should read Klein and Luna (2018), a comprehensive book about Brazil’s agricultural modernization.

Incidentally, it was surreal for me to read that induced innovation theory was the basis of Embrapa’s strategy. At one point, my own research focused on “directed technical change”, the modern successor to induced innovation as a concept. I only knew of it as an academic theory, and never imagined it was used as a policy playbook so successfully!

Interesting piece. Hayami and Ruttan book on induced innovation; also Hans Binswanger’s article in the 70s on technical change bias in agriculture. The cerrado soil research, IIRC, started in the 1950s. The African grass is Brachiaria (genus name is now Urochloa); it is something of a puzzle why Brachiaria has not taken off in humid areas of sub-Saharan Africa as it has in Brasil.